Dear reader,

This week, Strange Intimacies, my debut collection of essays officially turns a year old. There is much to celebrate, I think, but I’m writing this having just recovered from a soul-cleansing cry.

Earlier this week, I met with my therapist, Dr. R– who taught me that so much of the grief and anger I’ve accumulated over the years have been squared away in my body, without the catharsis of release. And she was right, of course.

It wasn’t enough that I could run a 5km when I felt the ragbag of emotions bottleneck inside me. It wasn’t enough that I made myself a hot cup of chamomile tea and screamed to the lyrics of Billie Eillish’s L’amour de ma vie in my bedroom. It wasn’t enough that I let myself eat three of those sea salt chocolate chip cookies – the ultra soft and chewy, warm from the oven kind – that my niece baked from scratch over the weekend. It wasn’t enough that I’d upped my dose of medication. The real work lay in paying attention, she said.

Right before our session ended, I told her, there was so much relief to this practice. But it was also enormously terrifying. Healing was about sitting down with oneself, locating the emotions where they emerged in the body, and giving them qualities. It feels heavy. It feels hot. It feels prickly. It's like acid in my stomach. It's blocking my airways. Most of the time, I'm not aware that it is the emotion that is making me feel a certain way, that it’s moving through my body like matter with a certain weight and viscosity – until I pay attention. All this is a new language.

It’s like a child that’s inside me, you see, locked in a room, screaming and crying for attention, I told Dr. R–. The version of me before that session would hear the banging on the door and say, Calm the fuck down! Can’t you see I’m busy here? I have a job to do, bills to pay, strangers to impress, forty pounds to lose. And then I’d hear the child’s wails turn into a whimper and then the banging on the door would stop. At least for a while.

In one of our sessions, Dr. R– asked, What if you open the door, what do you think will happen?

With my eyes closed, I approached the door, pushing it open little by little.

I see her. She’s just a little girl, I replied.

Do you recognize her?

She doesn’t have a face.

What else do you see? Is there anything you recognize?

She’s been here all this time, alone, invisible, neglected. I can see she’s hurting.

Can you tell me what the young girl needs the most right now?

She wants to curl up. She wants to be touched. She wants to be seen.

Can you try to give this little girl the comfort she needs at the moment?

Yes.

Can you let her curl up?

Yes.

Can you caress her?

Yes.

If you could say something to her, what would you tell her?

That it’s okay. She’s safe. I’m here. I see her.

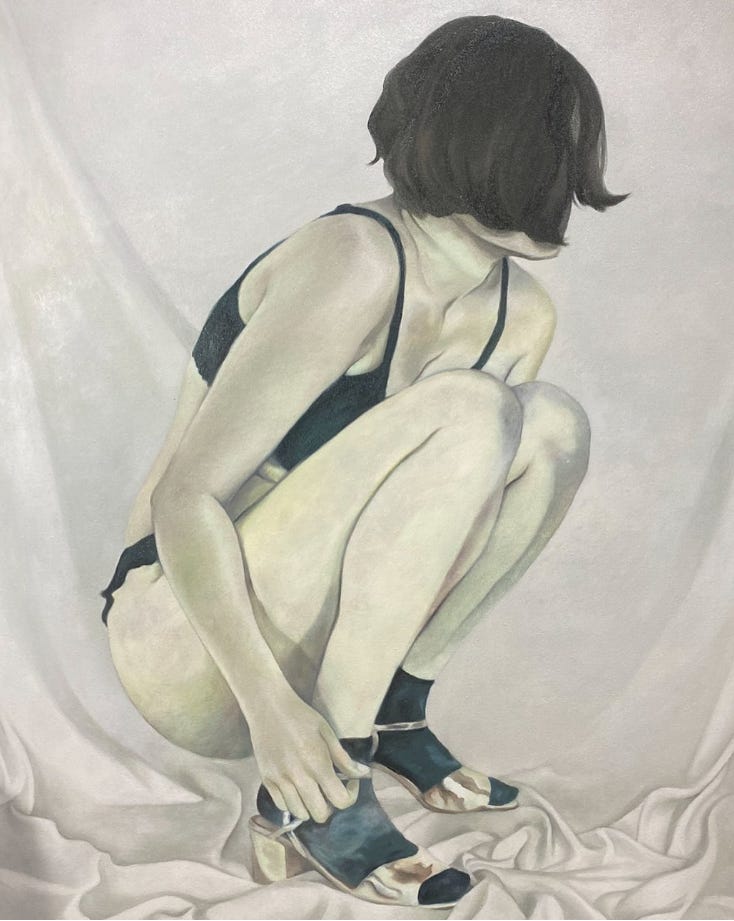

And then for a time, just silence. I could feel the tears running down my neck, caught in my lower lip like a rock pool of saltwater. And I witnessed myself at that moment coming to, without judgment: a lone, luminous figure of grief – my own body curled up in a fetal position; right hand pressed firmly to my chest.

The past year has been one of the most fulfilling years of my life as a writer. People tell me it was no easy feat to publish a book at twenty-six. I believe them. Many things coalesced to bring about that state of steady productivity, both good and bad: the imposed shutdown of the global pandemic, pursuing my MFA, and the fog finally clearing after years of therapy.

I long to say that publishing my book was a moment of clarity, but that wouldn’t be necessarily true. Although the writing of it has taught me a few lessons. One being that our sorrow doesn't vanish, but it can be remade. You write so it becomes a softer thing, something you can look at without flinching.

Another thing: it’s given me some understanding about how to pay attention. To attend closely is to uncover the threads of understanding that give way to tolerance, a kind of mercy, an allowance—if not for the world, then for ourselves, and all the fragmented selves that linger in time.

It is to witness the self in all its attempts—the messy, imperfect gestures toward meaning, toward connection, toward some version of completeness. But completeness, if it ever exists, is a fleeting state, a moment when the disparate parts align just long enough for us to feel at home in our skin.

So the self, endlessly incomplete, reaches outward, hoping that in the immense and indifferent chaos of the world, someone might take notice. It stretches itself thin in its longing, trying to find intimacy. And these attempts at intimacy—hesitant, graceless, sometimes ill-timed—are rarely what they could have been, rarely clean or perfect, and most often, strange. To reach outward is to believe, irrationally, that someone might accept us. It is an instinct older than reason, rooted in the deep, unspoken knowledge that we are, in essence, incomplete without the gaze. But is it not also the origin of a kind of belief?

It is to risk: I am here, messy and unresolved, and I hope you might hold me not with judgment, but with understanding.

In my body, the act of paying attention allows for grief to bloom like a flower, sprouting new roots, and unfurling to more areas within. It starts in the chest and inches its way even closer to the back, neck, and throat. I sometimes fear where the grief has yet to go. I distrust my capacity to bear it, but here’s the thing: grief asks nothing more but to be witnessed. To be seen as something that blooms, something with edges, something that longs to be held. And with a tentativeness, you hold it.

So to you, dear reader, I say: thank you for holding me and seeing me. And for, of course, giving Strange Intimacies a place at your bedside and slipping it quietly into the lives of your dearest family and friends.

Naiyak po ako sa pagbabasa. Hehe. Congratulations and all the flowers, Miss Zea! Grateful for your art. <3